There’s a vault of blue sky and a tinny chill to the sunshine today. Migration time! If I went to Newmarket Heath this afternoon, lay on the wiry turf and stared straight up, I'd see all sorts of birds flying much higher and with more purpose than usual: gulls, harriers, buzzards, perhaps an osprey or a peregrine.

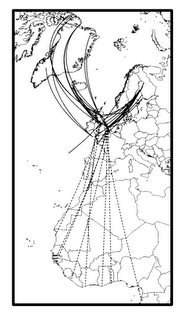

There’s a vault of blue sky and a tinny chill to the sunshine today. Migration time! If I went to Newmarket Heath this afternoon, lay on the wiry turf and stared straight up, I'd see all sorts of birds flying much higher and with more purpose than usual: gulls, harriers, buzzards, perhaps an osprey or a peregrine.I didn't understood this migration business until a few years ago. Not to say I didn’t know a lot about migratory flyways, proximate and ultimate causes, timings, ringing recoveries, and quite a lot about the history of those most romantic of ornithological sites, coastal bird observatories, where tank-topped 1950s ornithologists smoked pipes while they extricated warblers from mist-nets and ringed their tiny legs with numbered bands.

No, I ‘got’ migration in 1998. Isn't that a ridiculous sentence? Bear with me. I was visiting my friend Erin. He lives in Maine, in a house by the river, and right on the eastern coastal flyway. It was September. It wasn't hawkwatching that did it, although seeing Coopers and Sharpshinned hawks slip past mountain ridges is rather cool. Nor was it the little falls of warblers, bunched, damp and grey, sitting in the shrubbery at dawn.

I 'got' migration on a trip to Monhegan Island. Seven miles out to sea, Monhegan is famous for — oh, lots of things. Runes that record Viking outposts. An artistic outpost, too, home of the Wyeth family — no-one does better gulls than Jamie Wyeth, by the way —

Monhegan is rocky and lichen-y (lichenaceous?) and mossy and wet as a beach pebble even in the sun. It was fog-bound when we arrived, and the morning after. Erin and I walked up the hill behind the town as the mist cleared, and as it did, the sky filled with merlins. Carnival time! Merlins everywhere! And scores of passerines on the ground, crouching motionless behind stalks and stones. Fair enough: we found several tufts of feathers attached to torn scraps of skin stuck to rocks: remnants of fresh merlin kills. Warblers for breakfast.

Down by the sea, we walked right up to little groups of Least Sandpipers: ridiculously tiny, pebble-sized travellers resting here on their way south from the Arctic. They watched us incuriously down their long noses, as unconcerned about our presence three feet away as were the wet fronds of wrack they stood upon.

It was that morning, I think, that I felt for the first time (felt in my bones) the strange, seasonal lines of force pulling animals this way and that. A strong, inchoate need to move, but in concert with very precise feelings about how and where, a keen eye for weather and wind and fellow-feeling.

Of course, migration works both ways; yes, northern hemisphere birds migrate south in autumn. But it's south here, for some. One of my favourite birds — you see, I've finally got to the point — is a winter visitor to Britain. It's a thrush. A subarctic one.

Two species of thrushes visit Britain in winter. The smaller of the two is the redwing, a jaguar-like, shy, and slightly deranged thrush with devilish eyestripes and a burst of dried-blood rouge on each side. Redwings skulk in hedges and disappear with a thin seeeeep alarm call, and they slink about in the periphery of your vision when they first arrive.

But my favourite arctic thrushes are fieldfares. They're big, bold, patterned and arch. Alternatively, they're grey, fierce and wolfish.They are splendid. You have to use the plural, when talking of fieldfares. They arrive in rattling flocks like gusts of spray or hail. They are noisy when they fly, and their chak-chak-chak call is like someone launching a handful of pebbles on an iced-over pond surface. Chack chack chack: echoey, dopplery, cold.

Photo by Sergey Yeliseev

A very few pairs nest in the north of Scotland, right now. Most hail from Norway and Sweden and further north-east, and spend the winter being nomads, moving from place to place in response to snow and berry crops. In Britain they bounce about on playing fields, pasture and football pitches and eviscerate rotting apples in orchards with predatory relish. I love them also because they carry the arctic around them like coats. Different birds carry around place with them in different ways. They carry history, too.

There's much more to say on this, of course, of course. Here is a poem by R.F Langley that has fieldfares in it. I should probably not republish it here without permission, but perhaps Roger wouldn’t mind. He is the finest nature poet in Britain.

The Barber's Beard

By Wednesday afternoon the wind has dropped

and there can be a shakedown. When I tap

the stems, black seeds jump off onto the snow

and fix themselves, so Jack says, according

to the disposition of the stars. It's

Alexander's dust, he says. It smells of

myrrh It's Macedonian parsley and

also, he says, the surface of fresh snow

is more like fur. Each seed is caught in this

soft stillness as a small orb in its place,

tilting its face, and very tenderly

presented to the air. Now we expect

some music in the distance, from a house

which once was there.Yes, Crustyfoot, we guess,

has made it to Piepowder Fair, and so

we know that Scipio will soon be back

from Africa. He'll blow in from the north

on Scandinavian gales. He'll be disguised

as a big thrush, dancing and flapping in

the cold bathroom and shouting out, "I'm home!

I'm home!" Home in the roofless ruin up

the track, where Jack's map says "Old Hall" and all

the drifts are deep and new. So, in the glow,

thorn by thorn, another diagram of

the strategy of last year's brambles has

been drawn.I stop and stand where paths cross on

a Wednesday afternoon Where else am I?

Somewhere there is a story being told

I recognise Jack's voice that's quietly

telling it, as he describes how a man

is standing underneath a tree. How he

can see the standing of the man. He says

he feels his coat is comfortable and that

his shoes are doing well. The comfort of

his coat and what is watertight. He sees

that the ash is carrying its bunches

of ripe keys. The tree's carrying, and the

carrying of the keysThe amazement

of Scipio in his shaving mirror

Show me his shivering. Show me his quick

smile that flutters out about the edges,

and spreads as wide as the blue backs of what

must be a flock of fieldfares, suddenly

flashing round the lime-green branches of bright

winter hedges, and he....who?..we...at once

smell soap, and unexpectedly catch sight

of an awkward little grin attempting

to take flight, avoiding the circle of

reflected light. The only witness's

white face, frozen as he realises

that it's up to him. The him it's up to,

disabled by his role in last night's dream

and terrified that I am Hannibal.Dustyfoot arrested in a blaze of

alibis, blinking like an idiot

and hinting he's a friend of Jupiter.Are you all right? Is he all right? Here is

his list of all the dead elms in the ditch.

If you need to check the details you will

find the same old worn-out wormholes under

any scab of bark, and nothing about

the arrangements to tell you which is whichWell then. Good morning Jack. Don't slip away.

Just for a moment there I thought you'd gone

while I was shaving you. Please look on me

as if I were your barber, concealing

my irritation that you're late today

by gossiping along in this sing-song,

hiding the gist of what I have to say

in brisker chatter.Suppose the felties

were to pick out every berry, laughing

mysteriously,"Tchak, tchak!" That Jack himself

were the piper, and his son stole sweets. Which

silly little theft, for all the shouting,

turned out to be, not just a merry lark,

but princely, attended in the dark by

cherubim. Believe it. That the bodies

of the elephants rolled over on the

bitter snow. That schedules barked. That a freak

tide exposed the northern wall as they stormed

across the lagoon at CartagenaThen it would seem that all the answers could

be ticked As if the nouns, detected in

the depths, began to glimmer deeper yet

beneath the things, so all the secret eggs

grew wings and even Hercules was sure

his debts would settle out of court at last

Then keys could hang fast, waiting for a touch

in March from sleepy moonlight Scuttling verbs

could trap elusive opportunities

among unlikely rootsBut just as it

occurred to Jack that he might count the flock,

bird after bird displayed an ash-gray rump.

They've turned away and opened up.They areabout to go.This is the moment when,

flummoxed to know what else is left to do,

Jack and the poet and the pronouns shrug,

take a breath each, and melt into the blue.

3 comments:

I share your enthusiasm for Fieldfares, known as Felfers or Greyrumps on the Fens. Weather is mild, they are in the fields digging for leatherjackets. Weather is harsh, they are in the orchards feeding on fallen apples: or, if I am lucky, in my garden, feeding on the apples that I have thrown on the lawn. I once joined a ringing expedition to the Bristol area, where fieldfares were feeding on Sea Buckthorn berries, It was the only time I have seen birds the worse for drink.

Redwings are much more mysterious, as you say. They appear early in autumn on the field below my back garden, and then, phuttt, they are gone, and I don't see them again until late wintertime.

I hope you don't mind, Pluvialis, but you have inspired me to write something in my blog about my own epiphanic migration moment .

It's lovely. People, hie to Oldscroteshome and read it!

Oh now you've done it... MIGRATION MEME!

Post a Comment